|

CURRENT RESEARCH

A Poetics of Redemption For the past twenty years or so, much of my research and writing has been associated with the work of the Institute for Theology, Imagination and the Arts in the University of St Andrews, a Research Institute which I co-founded in 2000 with Jeremy Begbie and of which I served as Director from 2000 to 2013. My current major project is a work of three volumes engaging Christian theology in constructive conversation with other disciplines and practices clustered, for convenience, around the rubric of 'imagination and the arts'. This recognises that the capacities and contributions of human imagining are concentrated identifiably in the practices and products of human artistry, but insists that the imaginative dimensions of our humanity range far more widely in ways that are both distinct from and continuous with the artistic and 'creative' imagination. |

|

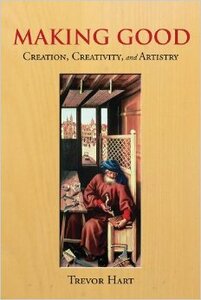

In October 2014 the first volume of this major work (which I have dubbed 'A Poetics of Redemption') was published. The larger project investigates the claim that imagination lies close to the heart of our creaturehood as human beings, and is thus central rather than peripheral to the trinitarian dynamics of God's redemptive engagement with us. Making Good: Creation, Creativity and Artistry (Waco, TX: Baylor University Press) situates an account of human 'creativity' within the parameters of a Christian doctrine of creation, and explores some of the theological tensions and resolutions involved in doing so. Human artistry, I argue, affords a concrete paradigm of our wider human calling to participate in God's own creative project, fashioning a world fit for our perpetual indwelling together with the one who is Father, Son and Holy Spirit.

|

|

I am currently working on the second part of this projected trilogy. Taking Flesh: Incarnation, Embodiment and Artistry will build directly on its predecessor. Based on explorations first undertaken in preparing the New College Lectures for 2015 (hosted by the University of New South Wales, Sydney) it will furnish a theologically informed account of another essential facet of human creatureliness—viz, its embodiedness, its situation in the world of matter, of bodies, of the ‘flesh’. A theological account of things is bound to resist the reduction of reality either to matter (as some forms of ‘materialism’ seek to) or to ‘spirit’ (as some forms of idealism seek to). A Christian account, I shall argue, is bound nonetheless to acknowledge their discrete levels of existence while yet grasping them only together and in the closest of relationships to one another, each, as it were, penetrating the other’s being within the warp and woof of creation. |

Within the dynamics of human existence and action in the world, I contend, matter and meaning are forever being woven together in new ways, their natural admixture lending itself naturally to creative reconfigurations in which each is needful to the other’s fullest existence and expression. Such an account will, of course, demand a careful reconsideration of some traditional valuations of human bodies relative to the world of things ‘spiritual’. It will need, too, to grapple seriously with that other connotation of ‘the flesh’, viz, 'creaturely' reality as distinct from God's own (a category which applies just as surely to the non-material elements of our humanity as to our fleshy extensions into geometric space), and with the fact that flesh-taking and meaning-making occurs within a world entangled in the bonds of sin and death, still struggling and groaning for its liberation. What, we shall have to ask, might a redemptive flesh-taking amount to and look like?

As its full title suggests, Taking Flesh will find its theological concentration and orientation in the Incarnation, the unique moment of flesh-taking in the life of God himself which both parallels and in some sense (and part of this book’s purpose will be to clarify in whatsense) furnishes the conditions for all those acts of creaturely flesh-taking and meaning-making alluded to above. That the Word or Logos of God finds its final expression and fulfillment vis-à-vis the creature by appropriating ‘flesh’ rather than remaining discarnate furnishes a vital theological limit-case in terms of which creaturely analogies may and should be weighed and measured.

The central thesis of this second part of the three volume set is thus that for God to be fully God in relation to the world he has created involves God in ‘taking flesh’ and making it his own in a redemptive reconfiguration and transfiguration of it, exalting it so that it becomes fully the bearer of the divine life of Father, Son and Holy Spirit. In an analogous and related manner, for the human creature to be fully human (and for the world to be fully ‘the world’ for us) involves us in repeated acts of ‘flesh-taking’ and ‘meaning-making’, of which the practices and products of artistry, albeit only one sphere in which this occurs, may function as a particularly appropriate paradigm, and furnish a set of instances and types consideration of which brings us quickly to reckon with the peculiar tensions and resolutions proper to the phenomena of our wider human being-in-the-world.

As its full title suggests, Taking Flesh will find its theological concentration and orientation in the Incarnation, the unique moment of flesh-taking in the life of God himself which both parallels and in some sense (and part of this book’s purpose will be to clarify in whatsense) furnishes the conditions for all those acts of creaturely flesh-taking and meaning-making alluded to above. That the Word or Logos of God finds its final expression and fulfillment vis-à-vis the creature by appropriating ‘flesh’ rather than remaining discarnate furnishes a vital theological limit-case in terms of which creaturely analogies may and should be weighed and measured.

The central thesis of this second part of the three volume set is thus that for God to be fully God in relation to the world he has created involves God in ‘taking flesh’ and making it his own in a redemptive reconfiguration and transfiguration of it, exalting it so that it becomes fully the bearer of the divine life of Father, Son and Holy Spirit. In an analogous and related manner, for the human creature to be fully human (and for the world to be fully ‘the world’ for us) involves us in repeated acts of ‘flesh-taking’ and ‘meaning-making’, of which the practices and products of artistry, albeit only one sphere in which this occurs, may function as a particularly appropriate paradigm, and furnish a set of instances and types consideration of which brings us quickly to reckon with the peculiar tensions and resolutions proper to the phenomena of our wider human being-in-the-world.

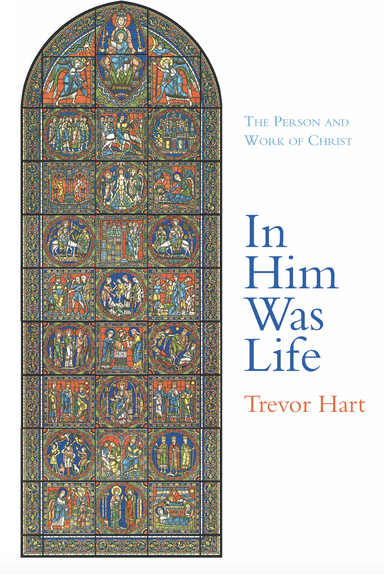

In Him Was Life: The Person and Work of Christ |

My most recent publication is a book on the person and work of Christ. This is based on scholarship conducted over the past thirty years, though many chapters published hitherto have been revised here for inclusion in what is identifiably a work bound together by a coherent set of themes and perspectives, and the book contains additional new material intended to meet the demands of a single volume on its subject.

The topic of Christology or consideration of the ‘person’ of Christ is often disentangled from his ‘work’ in systematic treatments to be tackled under a heading of its own. But unless handled with care this bit of doctrinal tidying can, the book suggests, be misleading and, in theological terms, potentially dangerous.

Humans, Christians contend, need to be rescued from a plight which currently distorts and ultimately threatens to destroy their creaturely well-being under God, but that lies utterly beyond their own control or influence. But just what sort of threat is this? By what means are we to think of it as having been met? And how should we think of all this in relation to the most radical and central Christian claim of them all, that meeting it has involved God in ‘taking flesh’, becoming one of God’s own human creatures and dwelling among us?

The history of Christian doctrine reveals a remarkable variety and diversity of answers to these questions, and this for a number of reasons. First, the biblical text itself (which furnishes the raw materials for the theological craft) offers a striking kaleidoscope of metaphors in its attempts to make sense of and develop the gospel message that ‘salvation’ is at hand. Second, these images have in turn been taken up, interpreted and developed within a vast range of different social and historical contexts, each bringing its distinctive questions, concerns and expectations to bear upon the text. And third, the Christological identification of Jesus as ‘God incarnate’ has been permitted varying degrees of purchase on the ways in which these images are unfolded and their entailments explored.

This volume is concerned with a series of core questions that arise when Christology and soteriology are deliberately ‘thought together’ rather than presumed to be patient of discrete treatment. How should we imagine and speak of what ‘salvation’ (itself an intrinsically negativeimage) finally means in positive terms if, indeed, in Jesus God has, as various theologians over the centuries have dared to suggest, not simply effected a cosmic salvage exercise but effected a ‘marvellous exchange’ in which God has become what we are so that we in turn might share in God’s own life? What does all this mean for our understanding of who God is, of our own creaturely nature and capacities, and of God’s ways of relating to us and realizing God’s own creative purposes? And, significantly, what might Christology itself have to say about the nature, possibilities and constraints of ‘theology’ (our thinking and speaking about God) itself? These questions are grappled with through a series of engagements with theologians across the centuries, including Irenaeus, Clement of Alexandria, Athanasius, Anselm, Calvin, P. T. Forsyth, Karl Barth, J. A. T. Robinson, T. F. Torrance and others.

Entitled In Him Was Life the book was published by Baylor University Press in October 2019.

The topic of Christology or consideration of the ‘person’ of Christ is often disentangled from his ‘work’ in systematic treatments to be tackled under a heading of its own. But unless handled with care this bit of doctrinal tidying can, the book suggests, be misleading and, in theological terms, potentially dangerous.

Humans, Christians contend, need to be rescued from a plight which currently distorts and ultimately threatens to destroy their creaturely well-being under God, but that lies utterly beyond their own control or influence. But just what sort of threat is this? By what means are we to think of it as having been met? And how should we think of all this in relation to the most radical and central Christian claim of them all, that meeting it has involved God in ‘taking flesh’, becoming one of God’s own human creatures and dwelling among us?

The history of Christian doctrine reveals a remarkable variety and diversity of answers to these questions, and this for a number of reasons. First, the biblical text itself (which furnishes the raw materials for the theological craft) offers a striking kaleidoscope of metaphors in its attempts to make sense of and develop the gospel message that ‘salvation’ is at hand. Second, these images have in turn been taken up, interpreted and developed within a vast range of different social and historical contexts, each bringing its distinctive questions, concerns and expectations to bear upon the text. And third, the Christological identification of Jesus as ‘God incarnate’ has been permitted varying degrees of purchase on the ways in which these images are unfolded and their entailments explored.

This volume is concerned with a series of core questions that arise when Christology and soteriology are deliberately ‘thought together’ rather than presumed to be patient of discrete treatment. How should we imagine and speak of what ‘salvation’ (itself an intrinsically negativeimage) finally means in positive terms if, indeed, in Jesus God has, as various theologians over the centuries have dared to suggest, not simply effected a cosmic salvage exercise but effected a ‘marvellous exchange’ in which God has become what we are so that we in turn might share in God’s own life? What does all this mean for our understanding of who God is, of our own creaturely nature and capacities, and of God’s ways of relating to us and realizing God’s own creative purposes? And, significantly, what might Christology itself have to say about the nature, possibilities and constraints of ‘theology’ (our thinking and speaking about God) itself? These questions are grappled with through a series of engagements with theologians across the centuries, including Irenaeus, Clement of Alexandria, Athanasius, Anselm, Calvin, P. T. Forsyth, Karl Barth, J. A. T. Robinson, T. F. Torrance and others.

Entitled In Him Was Life the book was published by Baylor University Press in October 2019.